Mini Project 4: Interactive Programming

Due: 12:00 pm, Tue 29 OctIntroduction

In the first three mini-projects you have written Python programs that do a wide variety of things. You have written code to analyze data (mini-projects 1 and 3), you have written code to make compelling visuals (mini-project 2), and you have written code to automatically download information from the web (mini-project 3). In this project we will be combining many of these threads. The big idea of this project will be to move from static programs (ones that are run, do some computations, and spit out a result) to interactive programs (ones that allow the user to perform actions that change the state of the program). The dance of user input and program response will enable us to write some very powerful software. Here are some ideas:

-

Interactive data visualization: as the amount of information available on the net explodes, there is an increasing need for tools that allow people to explore and understand the patterns in this data. During this exploratory stage, it is invaluable to have a tool that enables the user to rapidly explore various aspects and views of the data. Interactive visualization is an emerging and highly interdisciplinary field that straddles many disciplines including computer science, art, statistics, and even journalism. A potential SoftDes project in this space would be to write a program to download some data (or possibly acquire data in real-time, say from some sensor or a web API), display the data to the user in a clear and compelling format, and allow the user to dynamically explore various aspects of the data through a user interface.

-

Video games: video games are a clear example of an interactive program. A possible project in this space would be to develop a Python-based adaptation of your favorite game (classic arcade games or smartphone apps make ideal candidates). We encourage you to think broadly about using non-traditional input modalities (beyond keyboard and mouse). For instance, why not control a video game based on images captured by your laptop’s webcam?

-

Interactive art: a potential project in this space could be to create visuals or audio that is in some way responsive to the observer. The possibilities in this space are huge. One specific idea would be to create a computerized musical instrument that can be controlled through hand motions (where movements would be detected using computer vision).

This project will require you to design an interface for a user, so it’s important to consider who will be able to use your program. What limitations are there on who can use your program? Can you make the user experience more accessible for people with certain kinds of accessibility concerns: non-native English speaker, color blindness, or limited hand and wrist mobility, for example? Be intentional as a team about declaring the accessibility concerns you are accommodating in your interactive project and which you have chosen not to. Document accessibility decisions for your project reflection.

Deltas from Previous Projects

- You will be working with a partner on this project.

- This project is more open-ended than previous projects. In the last mini-project, you could choose the data and analysis tool that you wanted to explore. Here, not only do you have these choices, but you can also choose to make a very different thing (e.g. a video game versus an interactive data visualization).

- Your working repository on GitHub will be public instead of private at the end of the project, so it will become part of your professional portfolio visible to anyone on the web. We also encourage you to make your work on MP3 public, after receiving feedback and possibly making updates based on that feedback.

Computational Skills Emphasized

(some of these are only applicable to certain project topics)

- Object-oriented programming

- Event-driven programming

- Computer Graphics

- Physics Simulation

- Data visualization

Recommended Libraries

You are welcome to use whatever library you’d like for this project, however, there is a lot of benefit to sticking to the ones that we recommend. The best reason for doing so is to ensure that we, the teaching team, can provide you with as much support as possible as you use the library to complete the project. If you pick a non-standard library that none of us have used before, we will have a tough time helping you if you run into problems (although we will certainly try!).

Pygame

For 2D drawing, collision detection, and simple physics in Python, pygame is a fantastic choice. Perhaps the biggest strength of pygame is that it has many great tutorials as well as sample games to use as starting points (for example arcade games, puzzle games, and platform games).

Even though it might seem like odd choice, we are recommending pygame as the default library for those that are doing interactive visualization projects. There are fancier libraries out there, however, you can build some very nice interactive visualizations on top of the basic 2D drawing and mouse and keyboard event handling components in pygame. Further, using a fancy library reduces the amount of object-oriented code that you have to write, and in this assignment we want you to get a lot of practice writing your own object-oriented code. Sticking with a simple framework like pygame will support this learning goal nicely. A final advantage is that we will be doing at least one lengthy example in class that uses pygame. If you are using pygame for your data visualization project, you will get a lot more out of this in-class activity.

To install pygame, follow the instructions from the recipe page.

How to get started with pygame (these do not have to be done in this order):

- [if making a game] Go through the PyMan tutorials (part 1, part 2, part 3). It is shows how to implement a Pac-Man clone in pygame (don’t worry about the prerequisites section, you should already have the prerequisites satisfied). The strength of the tutorial is that there is lots of explanation of each part of the code. Unfortunately, the HTML formatting for parts 2 and 3 seems to be messed up, but hopefully these are still useful.

- Read through the pygame documentation.

- Read through the other pygame tutorials if you find one that seems more aligned with the project you want to create.

- [if making a game] Make sure you understand the basics of collision detection in pygame. Collision detection is a surprisingly tricky thing to write on your own, so it is recommended to utilize pygame’s built-in features for this (see this page). If you need to do collision detection with something besides rectangles, you may have to either adapt pygame’s collision detection or write your own collision detection routines.

OpenCV

If you want to use an input modality other than keyboard and mouse, you may find the computer vision library OpenCV useful. The idea here would be to capture images from a camera (probably the webcam on your laptop) and use those to control some aspect of your program. To get started check out the SoftDes Image processing toolbox. Next, read through the OpenCV Python tutorials and API reference).

To Implement, or not to Implement, that is the question!

There are some inherent trade-offs in using someone else’s whiz-bang library and coding the functionality yourself. Here are some pros and cons:

- Pro: using a library is faster and can let you do things in a short time that would be infeasible if you coded it yourself.

- Pro: you can mashup different libraries to do amazing things.

- Con: if you are shaky on your basic understand of Python, you may not learn the basics if you are relying too heavily on others libraries.

- Con: if you get too far down the path of using a library and it doesn’t do something important that you need, you are in a tough spot.

It’s up to you how heavily you want to utilize others libraries. All we ask is that you make the decision intentionally and with consideration of these trade-offs.

Project Ideas

Interactive Data Visualization

The first thing you will need to do is to get some data. Here are some sources:

- FiveThirtyEight: Nate Silver’s website on data-driven journalism. They have a GitHub repo with data they use in their articles!

- National Survey of Family Growth: Allen has a lot of examples that uses this database. To get started fork Allen’s

ThinkStats2repository. - Data.gov: a massive repository of data provided by the U.S. government.

- A very comprehensive listing of sources for open data.

- IBM’s Big Data for Social Good Challenge

- Make your own dataset using text mining (you should know how to do this from the last project).

- ??? (the possibilities are endless, e-mail us if you find an awesome trove of data that you think the class should know about post it to the course discussion forum).

Once you have the data you’ll want to think about how you might use visualization and user input to explore the data. To get your creative juices flowing, here are some cool examples of data visualization:

Spurious correlations, a humorous cautionary tale about data visualization

Check out the full listing from the New York Times Year in Interactive Storytelling. This link is for 2013, but other years are available.

Exploring How People Talk in Different Parts of the U.S. (source: New York Times Year in Interactive Storytelling 2013):

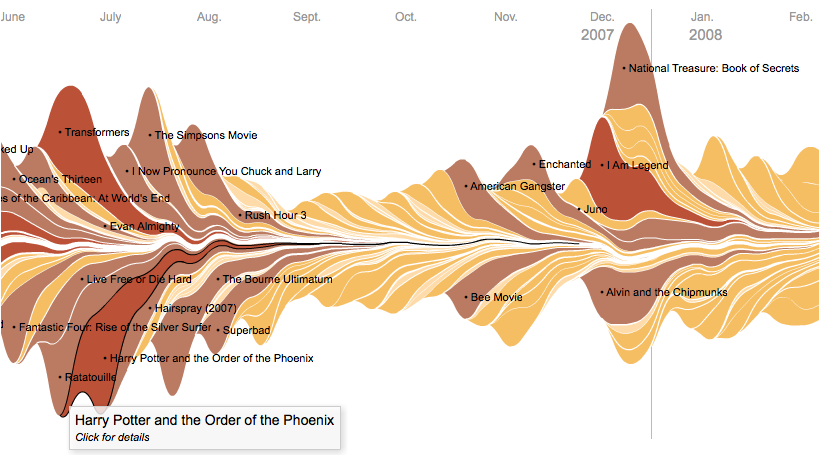

Exploring movie trailers (source: New York Times Year in Interactive Storytelling 2013)

Examining Box Office Hits:

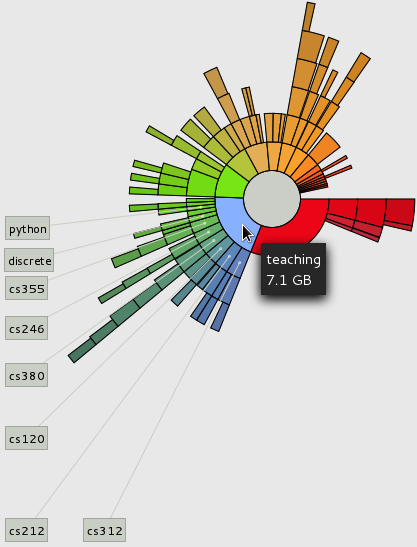

Where did my hard drive space go???

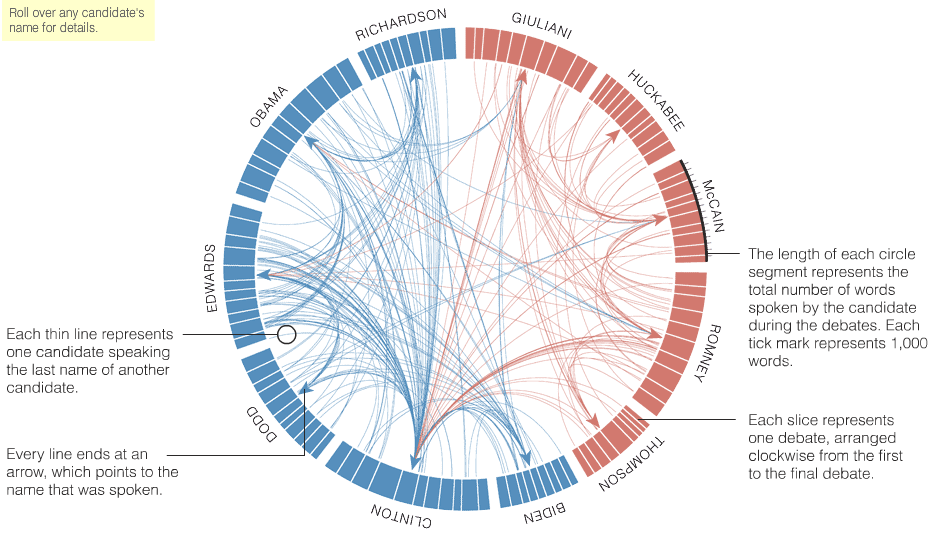

Examining the Group Debates:

Examining the impact of medicaid expansion (or lack thereof) state-by-state (source: New York Times Year in Interactive Storytelling 2013)

Arcade Games

If you decide to create a game, you should probably choose one that has relatively simple physics. Depending on how ambitious you are, you might want to stick to a game where all of the action is contained within a single screen. Here are some examples:

Missile Command (Wikipedia). This is the game John Connor plays in Terminator 2.

Pac-Man (Wikipedia)

SkyRoads (Wikipedia). Considerably more complex than the others, but maybe a simple version could be constructed.

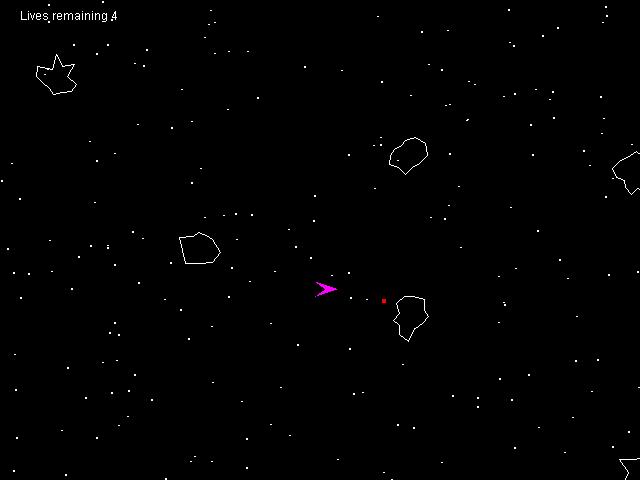

Asteroids (Wikipedia). This version was created in another computing class. Check out this video for the game in action plus some cool enhancements).

Q*Bert (Wikipedia). A popular arcade game in the ’80s; referenced in the movies Wreck it Ralph and Pixel.

Pogo Joe (Wikipedia). A Q*Bert “derivative”; written by Oliver Steele, who some of you may know from Olin.

Interactive Art

There is a big universe out there. Hooking up simple color tracking using OpenCV to sound synthesis is a nice one (e.g. a musical instrument controlled by movements). Check out the Wikipedia page for more ideas.

Design Guidelines

The big computational content of this unit is object-oriented programming. As a result, your code should make heavy use of objects! If you find that your design does not have any classes or just one, then there is probably something wrong. We will not be dictating / enforcing that you use any particular object-oriented design pattern. However, we are going to be explicitly scaffolding the use of a very powerful object-oriented design pattern called Model-View-Controller. Here is a diagram (from Wikipedia) that shows the various components of Model- View-Controller and how they interact:

To make things concrete, let’s think about how we might implement a Pac-Man clone. Here are the classes and the functions that you might use to implement your game:

Model: encodes the overall game state of the Pac-Man game (including level, position of pellets, position of Pac-Man and ghosts, etc.)- Provides an interface to the Controller to respond appropriately to user commands

- Handles collisions between Pac-Man and ghosts as well as Pac-Man and small and large pellets

PacMan: represents the player’s avatar in the game (a part of the model)- Provides an interface to respond to player actions as communicated by the controller (e.g. Pac-Man’s next move)

Ghost: represents a ghost in the game (a part of the model)Small pellet: represents a small pellet in the game (a part of the model)Large pellet: represents a large pellet in the game (a part of the model)Controller: handles commands from the user and manipulates the model appropriatelyPyGameView: draws the game state encoded by the Model to a pygame window

There are many ways to implement Model-View-Controller, so this is not the only way to operationalize Model-View-Controller in the context of Pac-Man. Remember, this is not the only way to structure your object-oriented design, but we hope it will be helpful at least as a jumping off point.

Project Deliverables

Getting Started

Due: Tue, Oct 15

Part of the Tuesday 10/15 class will be dedicated to developing and reviewing project proposals. Before launching into brainstorming project ideas, sit down with your partner and discuss the following guidelines:

- Share your personal learning goals for the miniproject

- Revisit preferred working styles with your partner (e.g. as captured in the reflection surveys)

- Discuss your expected commitment level to this project

- If you and your partner are not closely matched in terms of experience and comfort with programming in Python, you will want to make sure that you are both vigilant about avoiding some common pitfalls that occur with this type of team. The two most common pitfalls are: the person with more experience gets frustrated with the other team member and does all the work, and the person with more experience writes all the code while the person with less experiences watches them.

It’s OK and expected that you and your partner will have differences along some of these dimensions. We find it’s best to have a frank conversation early on about preferences and expectations, so that you can productively and respectfully work with each other throughout the project. Reach out to course staff if you’d like to some concrete suggestions for navigating differences.

After your teaming conversation, you can accept the assignment on GitHub classroom and form your team repository. Then you can each clone the shared repo to your computer and get started working on your proposal.

Project Proposal

Due: Tue, Oct 15

By the end of the day, your MP4 repo should have a proposal document (markdown or PDF, submit a link on Canvas) that describes the main idea of your project.

Your proposal document should address:

- What is the main idea of your project? What topics will you explore and what will you generate? What is your minimum viable product? What is a stretch goal?

- What types of users will your project be designed for (document potential accessibility issues)?

- What are your learning goals for this project (for each member)?

- What libraries are you planning to use? (if you don’t know enough yet, please outline how you will decide this question during the beginning phase of the project).

- What do you plan to accomplish by the mid-project check-in? (See below for some generic goals; edit to suit your particular project)

- What do you view as the biggest risks to you being successful on this project? How will you mitigate them?

Please do not just paste in these questions and answer them (you’re better than that). Instead, use them as guidelines to check for completeness as you draft a cohesive proposal document.

Completion of the proposal will comprise 5% of your grade for this project. Its purpose is to allow us to help shape your project in useful directions - and potentially adapt class-time to better prepare you for your journeys.

Note: You can/should start your project before instructors have seen your proposals.

Mid-Project Check-in

Due on or before: Tue, Oct 22

We are requiring an online mid-project check-in with course staff for this project. You may submit this check-in as soon as your team has made significant progress, but no later than Tue, Oct 22.

The mid-project check-in will comprise 15% of the final grade for this project. The grading for this check-in will be:

- 0% if you miss it or blow it off

- 50% if you have a write-up that offers minimal coverage to the prompts and points to barely-started work

- 100% if you demonstrate a concerted effort to get your project off the ground and cover the prompts below thoroughly (which can still be done concisely).

Given that different teams’ projects will be very different, there is no one set of things that are appropriate for you to have done by the mid-project check-in. Course staff will review your online check-ins and respond with written comments if necessary. Here are a list of fairly generic goals for the mid-project check-in that you will want to communicate to us:

- You should have good sense of the major classes that you will need to create for your project. A UML diagram (see Think Python) will be a useful thing to have as well.

- You should have a clear implementation plan. This includes how you will divide (or not divide) up the programming tasks among you and your partner.

- If you are planning to use a library that you read about, you should have verified that you can install it and that it can be used for the purpose that you want.

- You should have a good start on implementing some of the classes for your project.

Submit a text status update on Canvas addressing these generic goals and the specific goals you identified in your proposal, and pointing to concrete evidence of progress for each (i.e. links to work in your repository). This check-in must be submitted by Tue, Oct 22 at the very latest. If you’ve made significant progress before then we encourage you to submit earlier and get actionable feedback sooner.

Project Write-up and Reflection

Due: Tue, Oct 29

Please prepare a short document (~1 page not including figures) with the following sections:

Project Overview [Maximum 100 words]

Write a short abstract describing your project.

Results [~2-3 paragraphs + figures/examples]

Present what you accomplished. This will be different for each project, but screenshots are likely to be helpful.

Implementation [~2-3 paragraphs + UML diagram]

Describe your implementation at a system architecture level. Include a UML class diagram, and talk about the major components, algorithms, data structures and how they fit together. You should also discuss at least one design decision where you had to choose between multiple alternatives, and explain why you made the choice you did.

Reflection [~2 paragraphs]

From a process point of view, what went well? What could you improve? Other possible reflection topics: Was your project appropriately scoped? Did you have a good plan for unit testing? How will you use what you learned going forward? What do you wish you knew before you started that would have helped you succeed? If your project involved use of a data set, consider asking the same questions about alignment that you addressed in MP3.

Think about the people who could possibly interact with your project. Possible reflection topics in this space: What limitations are there on who can use your program? What would happen if someone for whom you have not designed your program uses it? What kinds of accessibility could be easily added to your project? Which would be difficult to implement or might dramatically change the user experience? Describe any design decisions made by your team regarding accessibility.

Also discuss your team process in your reflection. How did you plan to divide the work (e.g. split by class, always pair program together, etc.) and how did it actually happen? Were there any issues that arose while working together, and how did you address them? What would you do differently next time?

Turning in your assignment

Your code should submitted as either (a) Python file (or files) that can be executed by running e.g. python qbert.py, or (b) a Jupyter notebook.

Whichever option you choose, your code should have the elements of an organized structure in place. We expect that your final submission will be a proper program in which you define multiple well-thought out functions (rather than a basic script starting point with just a flat list of commands) and user-defined classes (e.g. following the Model-View-Controller pattern).

- If you submit a Python file:

- The project README must describe how to install any required packages (e.g.

pip install vaderSentiment) and how to run it (e.g.python qbert.py)

- The project README must describe how to install any required packages (e.g.

- If you submit a Jupyter notebook:

- You must test that it behaves correctly when you execute “Run All” from the “Cell” menu.

- You must also submit a Python text file.

Use the File > Download as > Python menu item to download a text file, and

git addit to your repo.

Just as for other mini projects, your code must be adequately tested and documented. Creating appropriate tests can be challenging for interactive programs; talk to course staff about strategies for your particular project idea. For documentation, you should include:

- Appropriate docstrings

- Comments inline in your functions

- README file that describes how to get your code to run

One way to ensure you have adequate docstrings is to generate documentation from them. You can do this using pydoc:

$ pydoc path/to/my_project.py

This will open a help file based on your docstrings (use q to quit). Make sure the help file would be useful to someone using your code, and feel free to attach it to your write-up as an appendix.

To submit your work:

- Push your completed code to your team Git repository

- Submit your Project Write-up/Reflection (1 per team, not 1 per person). This can be in the form of:

- a Markdown file, committed to your repository, or

- a PDF document pushed to GitHub, or

- a project webpage

- Complete your project README file. This is the first page people visiting your project will see, so it makes sense to spend a little effort on it.

- Submit a link to your work on Canvas